Art Talk with Barbara Ernst Prey

”Watercolor is a lot like jazz—there’s a lot of improvising and things happen that are unexpected.” — Barbara Ernst Prey

Visual artist Barbara Ernst Prey has served on the NEA’s National Council on the Arts since 2008. A distinguished watercolorist, Prey’s work has been collected by the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the White House, among others. As she shares in our interview with her, Prey developed her love of painting in the studio of her artist mother as well as in the many art museums she visited as a child. We spoke with Prey via e-mail to learn more about how she fell in love with the arts, her early work as an illustrator for The New Yorker and other magazines, and how painting helped her through a particularly hard time in her life.

NEA: What’s your five-word bio?

BARBARA ERNST PREY: World-renowned artist, naturalist, arts advocate

NEA: What do you remember as your earliest engagement with or experience of the arts?

PREY: My mother was head of the design department at Pratt Art Institute before I was born, so I grew up with a large studio in my home and a mother who was incredibly gifted and creative. I remember her outside at her easel painting and going on painting trips with her. She took me to the [Museum of Modern Art], the Whitney, and the Metropolitan Museum. Naturally I wanted to be like her. I learned so much from her. I remember painting in her studio on Saturdays listening to the opera where I had a table set up next to hers

NEA: What was your path to becoming a watercolorist?

PREY: I am known for my watercolors, but I also paint in oils and other medium. I always painted and drew. I think my first painting was in a juried show at age nine. My mother had Winslow Homer prints in her studio and art books all over. We also had the Whitney close by with their large selection of [Edward] Hopper works. I think I chose watercolor so as not to compete with my mother who was so good at oils. I painted while at Williams College and then started to do illustration work for such publications as The New Yorker (for ten years), The New York Times, and many other magazines. All along I was outside painting watercolors, which I have been doing for more than forty years. I have a style that is “distinctly my own,” as one curator put it, and I am trying to push the watercolor medium to new levels. Watercolor is a lot like jazz—there’s a lot of improvising and things happen that are unexpected.

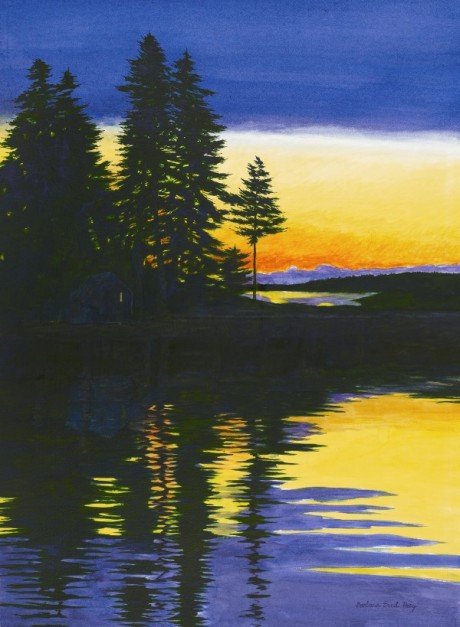

Nocturne IV

NEA: Are there specific pieces of work by other visual artists—or artists in any discipline—that have inspired/informed the way you approach your own work?

PREY: I was fortunate to study art history with Lane Faison at Williams, dean of the “Williams Art Mafia,” so I was able to do a lot of looking at great art. I would say the great American artists Homer, Hopper, and [John Singer] Sargent. I like [Charles] Demuth and [Frederic] Church’s watercolors and then there is the time spent in Europe on a Fulbright Scholarship when I studied [Albrecht] Durer and his use of line during my illustration work. I was fortunate to study the masters of European art and visit many museums, and then live in Asia as the recipient of a Henry Luce Foundation Grant. While in Asia I studied for a year with a Chinese master painter and absorbed the art of the East. However, I would again begin with my mother who instilled in me an appreciation of great art and artists and passed on her wealth of knowledge through her own art training.

NEA: Do you have a favorite painting of your own–in terms of subject, personal significance, etc.?

PREY: Each painting is unique and there is a problem solved or a problem worked through, a connection, a place, a story. Family Portrait is in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum and I painted it when my mother had Alzheimers and we were taking care of her. It was a way for me to express the unsettled nature of my life at that point. Perhaps the NASA paintings and the White House Christmas Card because they were such national commissions and very different for me: one is painting the universe and the other is painting an interior that will be seen around the world.

NEA: As you know we’re talking a lot about arts education these days. Why do you think arts education matters?

PREY: I am a very keen advocate of arts education. Just recently I worked with a sixth-grade class in an economically depressed area. Apparently it was a difficult school, but I didn’t notice. You could hear a pin drop—the students were so engaged. The arts open up new worlds and give you a tool that you will have with you for life, something that is inside of you. The arts are part of the fabric of who we are as human beings and speak to our soul. I am forever grateful for grade-school arts classes. I started playing the piano at age five, which has given me a great lifelong appreciation and love of music. It makes me sad when I hear that the arts programs are cut in schools. I think these decisions are short-sighted because they don’t realize all the side benefits of self-esteem, creativity, teamwork, problem-solving, directed “day dreaming,” as well as the wonderful way to detach from stress that the arts provide.

NEA: What’s your advice to young visual artists?

PREY: Try and see all the great art that you can, find your voice, and be sure that this is really what you want to do. I believe it is a calling and there is something in your DNA wired to be an artist.

NEA: You are a participant in the U.S. Art in Embassies (AIE) program with paintings in embassies all over the world. How do you think programs like AIE support our international diplomacy efforts?

PREY: My paintings have been on exhibit at the U.S. Embassy residences in Paris, Madrid, Prague, Oslo, and one hundred of my Patriot print are in U.S. Embassies and Consulates worldwide. I have been invited to lecture about American Art at the U.S. Embassies for their respective cultural communities where my paintings were on exhibit… and spearheaded a lecture program with the culture centers of Europe. I am excited that my painting The Collection was the invitation image for every U.S. Ambassador and Embassy worldwide for their Independence Day events.

I have been able to see first-hand how important the arts are because they cross borders and break down barriers particularly during my lectures and exhibits in Europe and Asia. There is a common language and shared interest and love for the arts that transcends political and other agendas.

NEA: You have also participated in the space agency’s arts program? What’s the link, for you, between art and science?

PREY: NASA commissioned me to paint four paintings. The Columbia Tribute and The International Space Station are currently on exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center, the The x-43 was just part of the NASA Art/50 Years SITES traveling exhibit. It has been an honor to be included with the artists invited to document space history but also to work alongside the scientists who are making it happen.

My mother was a painter and her sister a physicist who worked at MIT’s Lincoln Labs. I’ve seen this in my own family, bridging this perceived gap and all the more at a time when women didn’t really do this. Both are different ways of coming to an understanding of and explaining the unknown. Both provide an awe and wonder of the world, point in new directions, and provide answers and solutions in different ways. As my friend Ellen Futter, director of the American Museum of Natural History states, “Both science and art derive from nature and are but different lenses through which we endeavor to better understand and interpret the world around us and humanity’s place in it.”

NEA: What’s on your listening playlist right now? How about your reading list?

PREY: I always listen to music when I paint so I am a big NPR/WQXR fan here in New York. I have been listening to the Beethoven Symphonies, Bach organ music from my CD collection of concerts in Baroque churches, making my way through the Mozart symphonies and then for a break I go to jazz, music by my friends Jimmy Webb and Lee Greenwood, and on my iPod is my daughter’s play list—so I am slightly connected to the twenty-something group.

I am catching up on the books my friends who are writers have given to me: DNA: The Secret Life, which Jim Watson gave me and Jewell by former National Council on the Arts colleague Bret Lott.

NEA: Which artists—living or dead—would you invite to your fantasy dinner party, and why?

PREY: I recently came back from Florence so I would enjoy having Michelangelo at the dinner (who lived to be 89 so he would have a lot to say). I would be fascinated to hear how he worked. I would include Leonardo da Vinci to hear the conversation between the two. I like the way Leonardo’s mind worked. I would invite Albrecht Durer because his work was important when I was doing my line drawings for The New Yorker years ago. Fra Angelico has always been a favorite. Now we need some women….

NEA: As you know at the NEA, we say “Art works,” referring to works of art, the way the arts work on people, and also the fact that artists are workers who contribute to our economy. What does the phrase “Art Works” mean to you?

PREY: I have seen first-hand how art works whether it be someone taking one of my paintings back and forth to the hospital or someone with Lou Gehrig’s disease lining up my paintings on the fireplace to sit and contemplate.

Past cultures are often defined by their art; art is an integral part of who we are as human beings. Art nourishes us, encourages us, replenishes us, and fills us. It is something that touches the core of our being and brings out our humanity. Art often gives meaning to life and helps us explore who we are and why we are here. Art heals, produces joy, questions our comfort zone and makes us think, erases sorrow, and engages. Art can give meaning to life.